By weather forecasting we refer to the prediction of the future state of different components of the Earth as a system, such as the atmosphere and the ocean. To achieve this we need two ingredients:

- The current state of the components, also known as initial condition.

- A system that describes how the state evolves.

The current state of the atmosphere is obtained by gathering observations such as temperature, air pressure and wind speed. These observations come from a huge variety of sources including land weather stations, buoys, satellites, airplanes and many more, spread, unevenly, all around the world. It is worth keeping in mind that however many measurement devices are deployed, it is practically impossible to capture the exact state of the atmosphere at the level of particles.

On the other hand, the motion of the atmosphere and the ocean are described by equations that are valid for air and water, derived from physical reasoning and assumptions such as the conservation of mass or the basic laws of thermodynamics.

We know the equations, therefore we can solve them and derive the future of the state of the atmosphere, right? Wrong. These equations cannot be solved analytically, since they contain non-linear terms and instead we have to approximate them. In other words, we need to discretise the space in grid points and move from a continuous solution to a discrete one.

This discretised approach is implemented as a computer program and is the essence of numerical weather prediction; Given an initial condition, a computer simulates, approximately, the motion of the atmosphere and outputs it's future state. This process involves a significant amount of calculations, even to predict the future state of the atmosphere for a few seconds and is usually done by some of the world's most powerful super computers.

OK, so this all seems nice and well defined. Why aren't weather forecasts always perfectly accurate? There's a number of reasons:

- The atmosphere is a chaotic system, meaning that even slight changes in the initial conditions may lead to vastly different states in the future. This is more commonly known as the butterfly effect. Given that capturing the current state, as explained above, is inherently incomplete, we start off on the wrong foot.

- Since we can only approximate the motion of Earth system components, numerical weather prediction models have absolutely no idea what goes on in between grid points. This means that the spatial resolution of the grid of a NWP model is very significant.

- Numerical precision errors and limitations have a drastic effect on the quality of forecasts.

-

Weather forecasting is limited by the computational power. Weather models require enormous amounts of computing power to run, and even with the most advanced computers available today, it is not possible to run models at the highest resolutions over the entire globe in real-time.

Global forecasting models

So who has access to the observation data and the supercomputers to run the NWP software? Who can perform global weather forecasting?

There's a number of institutions that operate global numerical forecasting models. Some of these are:

- Global Forecast System (GFS), by the United States National Weather Service.

- European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF).

- ICON, by the German Weather Service.

Each of these global models varies in horizontal grid resolution, number of vertical levels, time step resolution, forecast lead time and update frequency.

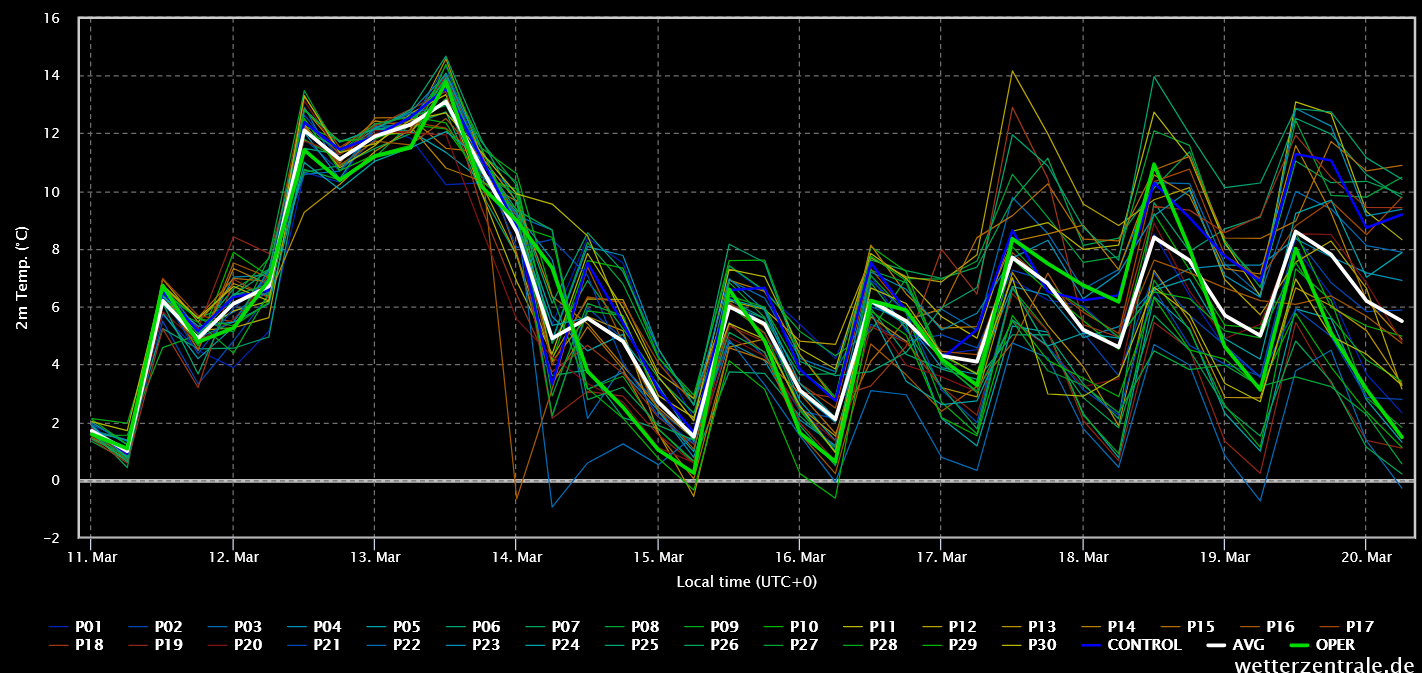

Ensemble forecasts

As discussed previously, both capturing the current state of the atmosphere, as well as computing it's evolution is imperfect. To reduce the uncertainty, a method called ensemble forecasting is often used, whereby the numerical weather prediction model is executed multiple times, each with slightly modified (perturbed) initial conditions. This set of forecasts aims to give an indication of the range of possible future states of the atmosphere. This comes at a high cost, as each run of the model requires separate computational resources.

Surface temperature ensemble forecast from the GFS model. Courtesy of wetterzentrale.de.

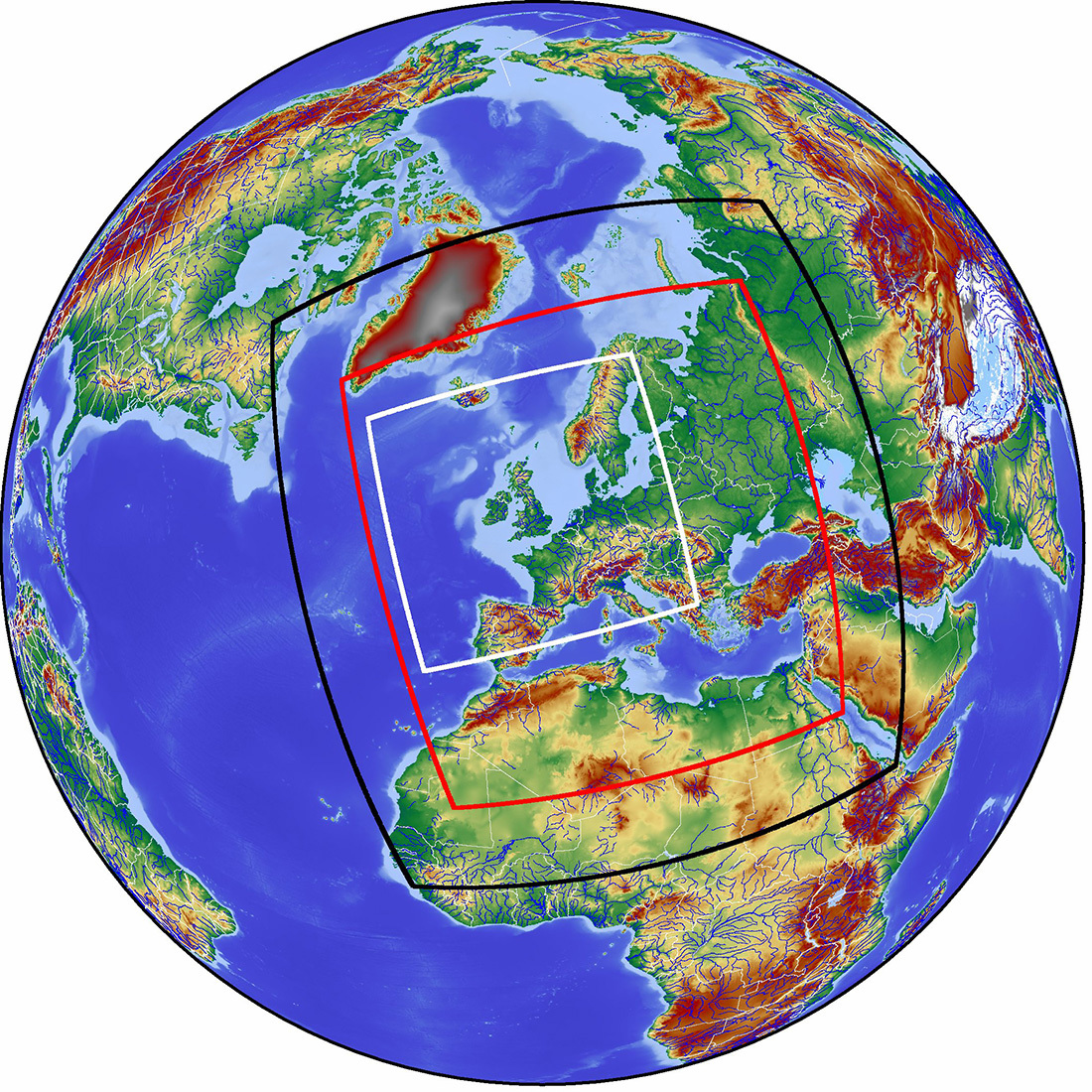

Regional models and the reason we need them to forecast the weather for renewables

The horizontal resolution of some of the most well known global models ranges from 6 to 25 kilometers, between grid points. As mentioned earlier, these models have no information about the state of the atmosphere, land and sea in between. Now imagine trying to forecast the speed the wind will be blowing on a wind farm, where the turbines are spread on a high peak just a few hundred meters apart from each other. The lower the spatial resolution, the more important local features are ignored, such as steep orography, local cloud formations etc.

Alright, but one would argue that the people at United States National Weather Service and ECMWF know their stuff. Can't they just increase the resolution of their models? No, because this requires immense computing power for global models. This is where regional models come to the rescue. A regional model, can be configured to produce forecasts in a, you guessed it, smaller region rather than the whole globe. This enables the operators of the regional model, depending on the computation resources available, to significantly increase the spatial and temporal resolutions of the produced forecast.

Regional weather models require input from global models for lateral boundary conditions. In other words, they need the global forecasts to tell them what is going on outside of the simulated region. This means that the resulting forecast of a regional model depends a lot on the source of the boundary conditions.

Arguably the most popular regional medium range forecasting model is WRF. It is an open source project with active development for decades, that is being utilized both operationally and for research.

What does Meteogen offer?

We operate regional weather models with:

- 1x1 km horizontal resolution

- More than 100 vertical model levels

- 10 minute time step

- 14 days forecast lead time

- Ensemble of regional models with lateral boundary conditions from GFS, ECMWF and ICON

- Forecast archive of at least 3 years

All these weather products are offered both as one combined forecast but also as separate pieces of data to include it in your forecasting pipeline. Moreover, due to the fact that we operate the models ourselves, we have the ability to fine tune the models at the exact location of your parks to further improve the forecast skill.

In a future post we will cover how Meteogen post processes the forecasts obtained from numerical models and how we use data assimilation and machine learning techniques to further improve the results.

Not convinced yet? You can give it a try, completely for free, no strings attached.